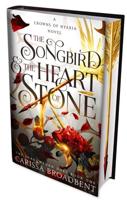

Publisher's Synopsis

Excerpt: ...the popular side. If, when the subject came into debate, Augustus should be sincere in the declaration to abide by the resolution of the council, it is beyond all doubt, that the restoration of a republican government would have been voted by a great majority of the assembly. If, on the contrary, he should not be sincere, which is the more probable supposition, and should incur the suspicion of practising secretly with members for a decision according to his wish, he would have rendered himself obnoxious to the public odium, and given rise to discontents which might have endangered his future security. But to submit this important question to the free and unbiassed decision of a numerous assembly, it is probable, neither suited the inclination of Augustus, nor perhaps, in his opinion, consisted with his personal safety. With a view to the attainment of unconstitutional power, he had formerly deserted the cause of the republic when its affairs were in a prosperous situation; and now, when his end was accomplished, there could be little ground to expect, that he should voluntarily relinquish the prize for which he had spilt the best blood of Rome, and contended for so many years. Ever since the final defeat of Antony in the battle of Actium, he had governed the Roman state with uncontrolled authority; and though there is in the nature of unlimited power an intoxicating quality, injurious both to public and private virtue, yet all history contradicts the supposition of its being endued with any which is unpalatable to the general taste of mankind. There were two chief motives by which Augustus would naturally be influenced in a deliberation on this important subject; namely, the love of power, and the personal danger which (150) he might incur from relinquishing it. Either of these motives might have been a sufficient inducement for retaining his authority; but when they both concurred, as they seem to have done upon this occasion, their united force...