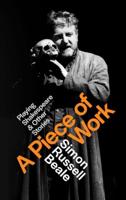

Publisher's Synopsis

Priscilla Batte, having learned by heart the lesson in physical geography she would teach her senior class on the morrow, stood feeding her canary on the little square porch of the Dinwiddie Academy for Young Ladies. The day had been hot, and the fitful wind, which had risen in the direction of the river, was just beginning to blow in soft gusts under the old mulberry trees in the street, and to scatter the loosened petals of syringa blossoms in a flowery snow over the grass. For a moment Miss Priscilla turned her flushed face to the scented air, while her eyes rested lovingly on the narrow walk, edged with pointed bricks and bordered by cowslips and wallflowers, which led through the short garden to the three stone steps and the tall iron gate. She was a shapeless yet majestic woman of some fifty years, with a large mottled face in which a steadfast expression of gentle obstinacy appeared to underly the more evanescent ripples of thought or of emotion. Her severe black silk gown, to which she had just changed from her morning dress of alpaca, was softened under her full double chin by a knot of lace and a cameo brooch bearing the helmeted profile of Pallas Athene. On her head she wore a three-cornered cap trimmed with a ruching of organdie, and beneath it her thin gray hair still showed a gleam of faded yellow in the sunlight. She had never been handsome, but her prodigious size had endowed her with an impressiveness which had passed in her youth, and among an indulgent people, for beauty. Only in the last few years had her fleshiness, due to rich food which she could not resist and to lack of exercise for which she had an instinctive aversion, begun seriously to inconvenience her. Beyond the wire cage, in which the canary spent his involuntarily celibate life, an ancient microphylla rose-bush, with a single imperfect bud blooming ahead of summer amid its glossy foliage, clambered over a green lattice to the gabled pediment of the porch, while the delicate shadows of the leaves rippled like lace-work on the gravel below. In the miniature garden, where the small spring blossoms strayed from the prim beds into the long feathery grasses, there were syringa bushes, a little overblown; crape-myrtles not yet in bud; a holly tree veiled in bright green near the iron fence; a flowering almond shrub in late bloom against the shaded side of the house; and where a west wing put out on the left, a bower of red and white roses was steeped now in the faint sunshine. At the foot of the three steps ran the sunken moss-edged bricks of High Street, and across High Street there floated, like wind-blown flowers, the figures of Susan Treadwell and Virginia Pendleton. Opening the rusty gate, the two girls tripped with carefully held flounces up the stone steps and between the cowslips and wallflowers that bordered the walk. Their white lawn dresses were made with the close-fitting sleeves and the narrow waists of the period, and their elaborately draped overskirts were looped on the left with graduated bows of light blue ottoman ribbon. They wore no hats, and Virginia, who was the shorter of the two, had fastened a Jacqueminot rose in the thick dark braid which was wound in a wreath about her head. Above her arched black eyebrows, which lent an expression of surprise and animation to her vivid oval face, her hair was parted, after an earlier fashion, under its plaited crown, and allowed to break in a mist of little curls over her temples. Even in repose there was a joyousness in her look which seemed less the effect of an inward gaiety of mind than of some happy outward accident of form and colour. Her eyes, very far apart and set in black lashes, were of a deep soft blue - the blue of wild hyacinths after rain. By her eyes, and by an old-world charm of personality which she exhaled like a perfume, it was easy to discern that she embodied the feminine ideal of the ages.