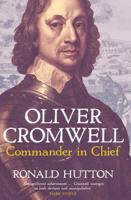

Publisher's Synopsis

The breaking off of negotiations was followed on both sides by preparations for immediate war. Hampden, Pym, and Holles became the guiding spirits of a Committee of Public Safety which was created by Parliament as its administrative organ. On the twelfth of July 1642 the Houses ordered that an army should be raised "for the defence of the king and the Parliament," and appointed the Earl of Essex as its captain-general and the Earl of Bedford as its general of horse. The force soon rose to twenty thousand foot and four thousand horse; and English and Scotch officers were drawn from the Low Countries. The confidence on the Parliamentary side was great. "We all thought one battle would decide," Baxter confessed after the first encounter; for the king was almost destitute of money and arms, and in spite of his strenuous efforts to raise recruits he was embarrassed by the reluctance of his own adherents to begin the struggle. Resolved however to force on a contest, he raised the Royal Standard at Nottingham "on the evening of a very stormy and tempestuous day," the twenty-second of August, but the country made no answer to his appeal. Meanwhile Lord Essex, who had quitted London amidst the shouts of a great multitude with orders from the Parliament to follow the king, "and by battle or other way rescue him from his perfidious councillors and restore him to Parliament," was mustering his army at Northampton. Charles had but a handful of men, and the dash of a few regiments of horse would have ended the war; but Essex shrank from a decisive stroke, and trusted to reduce the king peacefully to submission by a show of force. But while Essex lingered Charles fell back at the close of September on Shrewsbury, and the whole face of affairs suddenly changed. Catholics and Royalists rallied fast to his standard, and the royal force became strong enough to take the field. With his usual boldness Charles resolved to march at once on the capital and force the Parliament to submit by dint of arms. But the news of his march roused Essex from his inactivity. He had advanced to Worcester to watch the king's proceedings; and he now hastened to protect London. On the twenty-third of October 1642 the two armies fell in with one another on the field of Edgehill, near Banbury. The encounter was a surprise, and the battle which followed was little more than a confused combat of horse. At its outset the desertion of Sir Faithful Fortescue with a whole regiment threw the Parliamentary forces into disorder, while the Royalist horse on either wing drove their opponents from the field; but the reserve of Lord Essex broke the foot, which formed the centre of the king's line, and though his nephew, Prince Rupert, brought back his squadrons in time to save Charles from capture or flight, the night fell on a drawn battle.