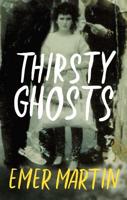

Publisher's Synopsis

The boys' desks, transferred from their old class-room, stood in a three-sided square in the centre of the museum, while Mr. Dutton's table, with his desk on it, was in the window. The door of the museum was open, so too was the window by the master's seat, for the hour was between four and five of the afternoon and the afternoon that of a sweltering July Sunday. Mr. Dutton himself was a tall and ineffective young man, entirely undistinguished for either physical or mental powers, who had taken a somewhat moderate degree at Cambridge, and had played lacrosse. By virtue of the mediocrity of his attainments, his scholastic career had not risen to the heights of a public school, and he had been obliged to be content with a mastership at this preparatory establishment. He bullied in a rather feeble manner the boys under his charge, and drew in his horns if they showed signs of not being afraid of him. But in these cases he took it out of them by sending in the gloomiest reports of their conduct and progress at the end of term, to the fierce and tremendous clergyman who was the head of the place. The Head inspired universal terror both among his assistant masters and his pupils, but he inspired also a whole-hearted admiration. He did not take more than half a dozen classes during the week, but he was liable to descend on any form without a moment's notice like a bolt from the blue. He used the cane with remarkable energy, and preached lamb-like sermons in the school chapel on Sunday. The boys, who were experienced augurs on such subjects, knew all about this, and dreaded a notably lamb-like sermon as presaging trouble on Monday. In fact, Mr. Acland had his notions about discipline, and completely lived up to them in his conduct.Having told Blaize to get on with his home-letter, Mr. Dutton resumed his employment, which was not what it seemed. On his desk, it is true, was a large Prayer-book, for he had been hearing the boys their Catechism, in the matter of which Blaize had proved himself wonderfully ignorant, and had been condemned to write out his duty towards his neighbour (who had very agreeably attempted to prompt him) three times, and show it up before morning school on Monday. There was a Bible there also, out of which, when the Sunday letters home were finished, Mr. Dutton would read a chapter about the second missionary journey of St. Paul, and then ask questions. But while these letters were being written Mr. Dutton was not Sabbatically employed, for nestling between his books was a yellow-backed volume of stories by Guy de Maupassant. . . . Mr. Dutton found him most entertaining: he skated on such very thin ice, and never quite went through.