Publisher's Synopsis

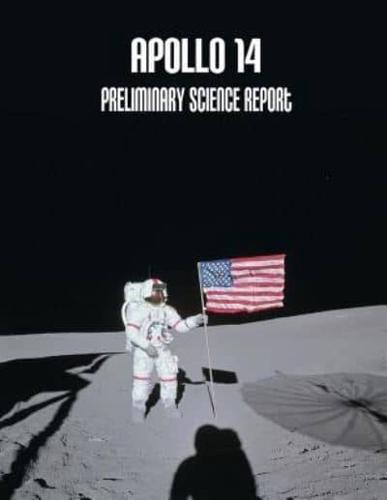

The third manned lunar landing, which increased to almost 200 the man-hours spent by astronauts on the Moon's surface, differed in character from previous missions. The dominant aspect of the first landing was, simply, that it was done. The second landing was notable for the precision that brought a manned spacecraft to rest 183 m from its target site, a robot spacecraft dispatched to the Moon two and a half years before. But the outstanding characteristic of the third landing, when Antares came down to the rolling foothills of Fra Mauro, was the exceptionally rich harvest in lunar science that the mission achieved. At Fra Mauro, astronauts Shepard and Mitchell emplaced an automatic geophysical station that quickly began to work in harness with Station 12, already functioning 181 km to the west, forming a valuable network that permits simultaneous observation from physically separated instruments. They also made a traverse on foot of record extent in an area of extreme geologic interest and brought back to Earth data and core tubes and other geologic samples in unprecedented volume. The preliminary scientific results reported in this publication are the product of work performed in the months immediately following the mission. Unquestionably these analyses and interpretations will be expanded and refined during the months and years to come. Apollo 14, the third mission, during which men have worked on the surface of the Moon, was highly successful. With the understanding of the lunar environment achieved by Apollo 11 and the pinpoint-landing capability demonstrated by Apollo 12, the Apollo 14 landing could be planned for a much rougher area of the Moon and one of prime scientific interest. This mission to the Fra Mauro Formation provided geophysical data from a new set of instruments located at latitude 340' S, longitude 1727' W. The Apollo 12 lunar-surface experiments package deployed in November 1969 is still functioning at latitude 311 ' S, longitude 2323' W, in the Ocean of Storms approximately 180 km from the Apollo 14 landing site. Comparisons between data from these first two sites in the Apollo scientific network can now be made. As an example, a single known seismic event, such as the impact of the lunar module ascent stage on the surface of the Moon, resulted in positive indications at both sites. The topography in the landing area was extremely interesting, and the geological and geochemical returns were great. Because of improved equipment, such as the modularized equipment transporter, and because of the extended time spent on the lunar surface, a large quantity and variety of lunar samples were returned to Earth for detailed examination. New information concerning the mechanics of the lunar soil was also obtained during this mission. In addition, five lunar-orbital experiments were conducted during the Apollo 14 mission, needing no new equipment other than a camera. The experiments were executed by the command module pilot in the command and service module while the commander and the lunar module pilot were on the surface of the Moon. This report is preliminary in nature; however, it is meant to acquaint the reader with the actual conduct of the Apollo 14 scientific mission and to record the facts as they appear in the early stages of the scientific mission evaluation. As far as possible, data trends are reported, and preliminary results and conclusions are included. Large numbers of samples and quantities of data must yet be examined and the results compared with the scientific information resulting from the Apollo 11 and 12 missions before any final conclusions can be drawn.