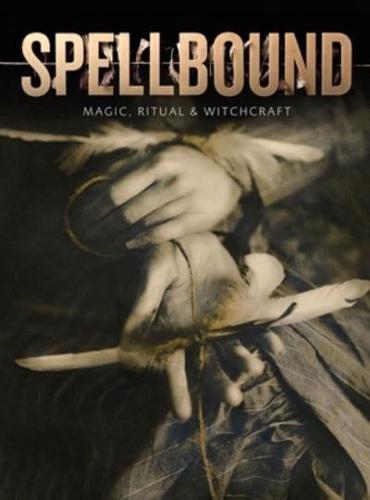

Publisher's Synopsis

Do you believe in magic? Even if you don't, you probably 'think magically' sometimes. We touch wood to stop bad things happening, or take a lucky object to a job interview or exam in an irrational attempt to influence the outcome. Spellbound: Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft was the first exhibition to examine how magical thinking has been practised over the centuries. With exquisitely engraved rings to bind a lover, enchanted animal hearts pierced with nails, mummified cats concealed in walls and many other intriguing objects, the exhibition catalogue shows that the use of magic is driven by our strongest emotions: the need to be loved, our fear of evil and the desire to protect our homes. Authors explore the practice of magic in the medieval universe, the early modern community and the modern home. While belief in magic and rituals can be comforting, it also led to the persecution of women as witches. This book examines both the idea of the witch and the reality of how women were accused of witchcraft. Even today, our tendency to think magically has not changed as much as we might think. Some of the chapters discuss contemporary ideas about magical thinking and the artworks produced especially for the exhibition to make connections between the ideas and experience of magic in the past and in the present.

Contents: Introduction - Sophie Page and Marina Wallace; Love in a Time of Demons: Magic and the Medieval Cosmos - Sophie Page; Musica Universalis - Harmonia Mundi and Hayden - Chisholm's Medieval Jukebox - Marina Wallace; Concealed and Revealed: Magic and Mystery in the Home - Owen Davies and Ceri Houlbrook; The Fear and Loathing of Witches - Malcolm Gaskill; Modern Rituals and Magical Thinking - Ceri Houlbrook; Installations by Contemporary Artists - Marina Wallace